Robots in the Age of Digital Surveillance, Digital Surveillance in the Age of Robots

An article by Matthew Guariglia, Policy Analyst, Electronic Frontier Foundation

Your information is not your own, not anymore.

It is collected on a second by second basis by your cell phone, your computer, by the microphone in your digital speaker, by the security camera on your office building, by the automated license plate reader you never noticed at the intersection — and all of it is stored somewhere. But increasingly, the collector and hoarder of data on your location, your purchases, your life, also is no longer the sole owner of that information. The information landscape is a hellish and paranoia-inducing array of data sharing. Companies sell your information on a vast data broker marketplace. Police harvest information from the consumer companies you use every day with simple requests, overly broad warrants, or data sharing agreements. Companies with profitable contracts from law enforcement agencies are increasingly given access to government data with the promise of using algorithms to find unseen patterns in the already-skewed collections of crime statistics.

Already as a society we’re seeing the fallout of these entanglements. Data brokers purchased the geolocation data of Muslim dating and prayer app’s users and sold it to U.S. military contractors. Fears abound that private companies that provide automated license plate readers to both police departments and private neighborhood associations could tap their entire network in order to help states prosecute abortion seekers. Police can even request emergency access to commercial home surveillance cameras without a warrant or the user’s consent by going directly to the company.

Even home devices like refrigerators are increasingly becoming “smart” and equipped with microphones and cameras are collecting data. It’s bad enough we may now have to live in fear that our refrigerator will keep track of what we eat and sell that data to food advertisers, but in 2018 we also heard news about how intelligence agencies in the U.S. and U.K. had the capacity to take control over the voice recognition system in smart TVs.

The more the private data storage servers of massive companies like Amazon and Google double as the evidence room for police departments and other law enforcement agencies, the more likely your data will be scrutinized in criminal investigations. Newly but increasingly popular warrants like Geofence or reverse keyword search warrants mean that, rather than requesting information pertaining to a particular suspect, police send requests to companies for data on anyone whose cell phone happened to be in the vicinity of an incident, or that anyone who Google searched the address of a store that was later burglarized might become a prime suspect.

As if this noxious brew of data sharing, law enforcement, and the potential for violence and arrest weren’t complicated enough, enter a new element: robotics. Robots and drones, whether they are autonomous or remote-controlled, are machines that collect data and run on collected data. How will these new rolling and flying data machines interact with a landscape already designed to rob people of their privacy? What new concerns will they raise as they become increasingly used in a world where consumer and law enforcement data are so enmeshed?

Let’s start with where we are at our current moment. Concern over police use of robots and drones is not the product of watching too many science fiction movies. You don’t have to be convinced that a Skynet takeover is imminent in order to be frightened about a near future where law enforcement readily uses robots or relies on data collected by robots. For those who have been watching police departments and consumer technology markets closely, this is not a sensationalist fear. It’s also not a few years away. It’s not hypothetical. It’s here.

Remote controlled drones are being purchased in large quantities by police departments for the purposes of “situational awareness” or being dubbed “force multipliers.” Inside homes, companies are eager to sell you drones and robots armed with microphones and cameras which collect data about the layout of your home in order to better patrol your living space. Both police departments and private entities are currently deploying autonomous robots searching for “suspicious behavior,” collecting data, or just generally acting as rolling “HELP” buttons.

Even though robots are already patrolling our streets, parks, malls, and grocery stores, we must wrestle with the complicated ways that they impact our civil liberties. By both collecting massive amounts of data or by legitimizing other massive surveillance operations by relying on that data to operate, the wide-spread use of robots and drones represent a new front in the war for privacy. And this doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of what happens to police or private actors arm those robots.

Robots that Aid Surveillance

While they are still rare, robots often present police or private entities hoping to outsource some patrolling to machines with the advantage of novelty. Not many people know yet what their capabilities are or what kind of data they collect.

Take Knightscope robots, for instance, autonomous rolling machines that are already out in the world patrolling parks, malls, and parking garages. While the company makes it a point to talk about the good press the robots engender through selfies and media mentions, a more concerning element is their ability to collect a massive amount of data. In addition to video and audio, the robots are also capable of reading license plates and have wireless technology “capable of identifying smartphones within its range down to the MAC and IP addresses.”

“When a device emitting a Wi-Fi signal passes within a nearly 500 foot radius of a robot,” the company once explained on its blog, “actionable intelligence is captured from that device including information such as: where, when, distance between the robot and device, the duration the device was in the area and how many other times it was detected on site recently.”

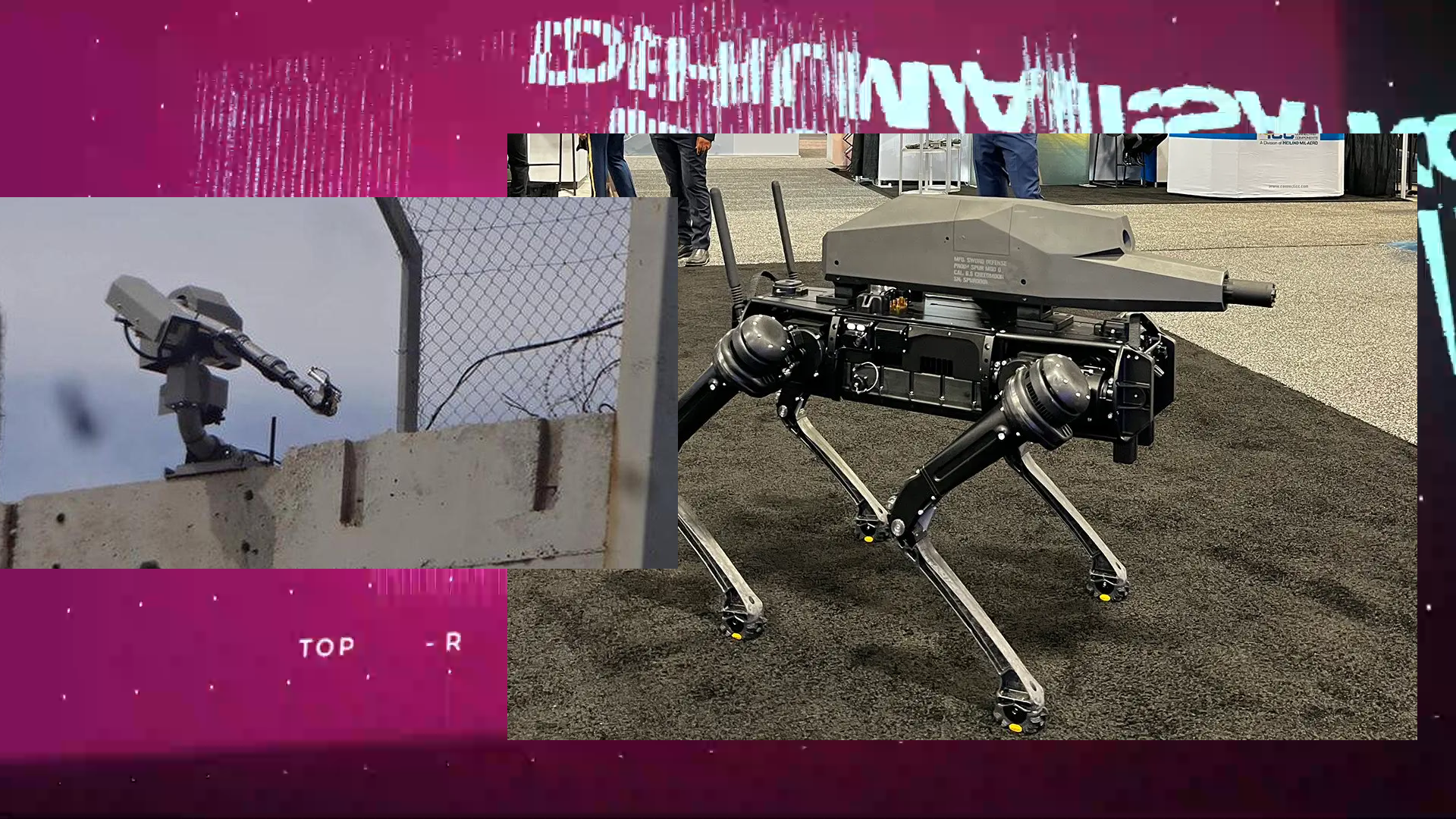

The truth is when autonomous robots–or even autonomous vehicles–are expected to traverse the world, they must rely on an untold number of cameras and sensors to make sure they don’t bump into anything or hurt anyone. In some cases, these sensors are very explicitly deployed by authorities to conduct surveillance. That’s why the Department of Homeland Security is currently considering deploying robot dogs loaded with sensors to patrol remote swaths of the U.S.-Mexico border as part of a much larger infrastructure of border surveillance. But in other cases, the sensors and cameras that enable autonomous movement became part of the police surveillance apparatus as a kind of happy accident.

We often say, if you collect enough data about people, eventually police will come asking for it. That is certainly the case with autonomous cars which are capable of cruising around cities collecting footage from multiple angles like a roving surveillance camera. This was true of the now-on-the-road self-driving cars currently cruising through the streets of San Francisco. Reporting from mid-2022 showed how the San Francisco Police Department has already requested footage collected from those cars “several times.”

As if fleets of rolling cameras with untold amounts of video footage sitting on servers accessible to police was not enough of a privacy nightmare, what happens when all of the footage from autonomous machines becomes searchable through biometric analytics? We’re not far off. Tesla has already experimented with facial recognition both inside and outside of their vehicles.

Whether it’s an autonomous car rolling through a neighborhood, a patrol robot logging your phone’s presence in a park, one benefit robots present is their access to people without arousing suspicion that police may not be able to get. This is one major concern about household drones and robots being sold commercially. What happens If police want to search a person’s home–and rather than presenting the warrant to the homeowner, they present it to a company in exchange for remote access to a household drone or robot? Household devices like those may present a brand new scenario in which police can search homes without ever entering them–and potentially without the companies letting you know your device has been commandeered.

The rise of robotics is not happening coincidently with the exponential rise in digital surveillance. The two are inextricably linked. That means not only are robots aiding the erosion of your privacy–but the vast amount of data being collected on you is also a chief enabler in the expanded use of police and commercial robots.

Surveillance that Aid Robots

We’ve seen how robots aid the project of mass surveillance–conducted by both companies, government agencies, and the two working in tandem. The question for the next 10 years will be: what will robots, drones, and drone operators be able to do with this much information?

Already, it’s clear that the autonomy of devices is contingent on a massive amount of data. In addition to sensors that, for instance, allow a robot to avoid hitting a wall, consumer robots designed to traverse your house also must make a digital map of that house.Only time will tell how and when police will request access to this type of data from the companies that maintain it.

With police collecting so much information on people, and potentially having access to all of the data companies collect as well, only time will tell how that knowledge will inform police use of even remote-controlled drones and robots. In Chula Vista, California, police are piloting a program in which remote-controlled UAS (unmanned aerial systems) respond to 911 calls. As of now, that program is reliant on people actively calling to first responders, but what happens when a similar program relies on surveillance to dispatch a fleet of autonomous drones no longer tied to trained operators? Programs like this may be much closer than you think.

ShotSpotter, a company which puts up high-powered microphones in hopes of detecting and triangulating gunshots in order to alert police, has already said they would be teaming up with a drone company to dispatch autonomous drones to fly automatically to the presumed site of gunfire. Reports have questioned just how accurate this type of technology is and raises the concern that drones, as well as armed police, could be swarming an area only to find people in the vicinity of a car backfire or fireworks going off. Surveillance technology automatically dispatching drones to a scene also invites us to think about the next scenario: how long until the police will want to arm those drones?

The Crossed Uncrossable Line: Armed Robots

Proposals for armed robots, especially robot-controlled armed robots as a response to crisis situations or alerts provided by surveillance technologies are surfacing every day. In 2022, Axon had to back away from a plan to deploy remote-controlled drones armed with tasers as a solution to school shootings when a majority of its ethics board resigned as a result of the proposal. Given the rise of proposed uses of autonomous weapons systems around the world, allowing weapons–be it guns, tasers, or bombs, on remote-controlled robots and drones might just be the green light needed for authorities to start consider automating those systems. And while some robot makers like Boston Dynamics say they will never arm their robots, other popular companies like Ghost Robotics, the company working with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, seems to be much less squeamish about armed robots.

Conclusion

If you were concerned about the rise of policing by robot, but felt that there was no way that ubiquitous surveillance could really affect your life– think again. Likewise, if you consider yourself part of the fight for privacy, but thought the threat of armed robots seems far-fetched, it’s time to consider how those two trends are intrinsically linked.

The pieces are all in place. Over the last few years we’ve seen how consumer privacy issues and government surveillance have merged in troubling ways–and the increasingly large role robotics are playing in that process. Now is the time to be standing up and demanding more control over the technology your police department has access to, regulations and protections of consumer privacy, and strict moratoriums on the use of armed robots. The future is here and we’re ready to fight the multi-pronged campaign necessary to make sure it’s an equitable one.

Learn more about Digital Dehumanisation

About Matthew Guariglia:

(Extract from EFF)

Matthew Guariglia is a policy analyst working on issues of surveillance and policing at the local, state, and federal level. He received a PhD in history at the University of Connecticut where his research focused on the intersection of race, immigration, U.S. imperialism, and policing in New York City. He is the co-editor of The Essential Kerner Commission Report (Liveright, 2021) and his bylines have appeared in NBC News, the Washington Post, Slate, Motherboard, and the Freedom of Information-centered outlet Muckrock. Matthew is an affiliated scholar at University of California, Hastings-School of Law and serves as an editor of “Disciplining the City,” a series on the history of urban policing and incarceration at the Urban History Association’s blog The Metropole.