Visualizing Palestine’s “Killer AI” story and the power of digital storytelling

An interview with Nate Wright

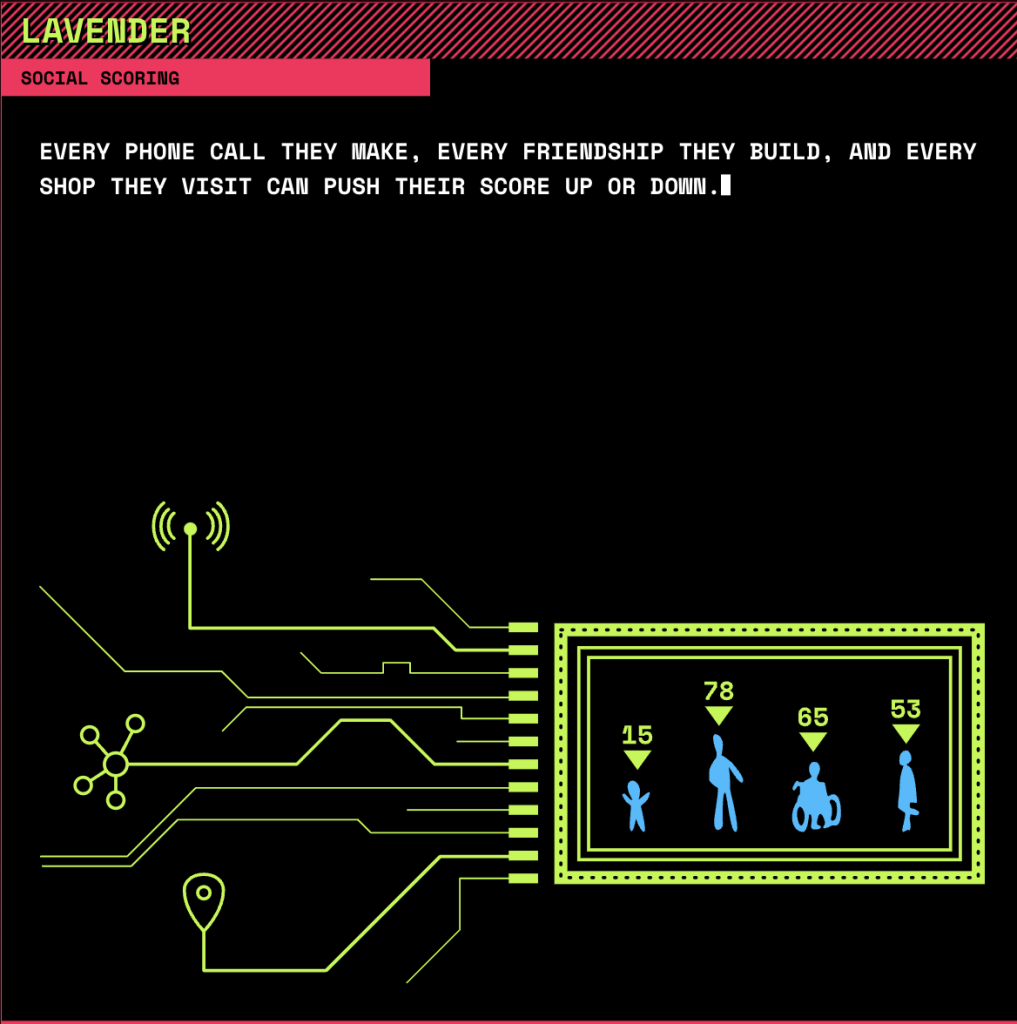

In response to the news that the Israeli Army was using the Lavender decision support system to generate, and subsequently strike, human targets in Gaza, Visualizing Palestine created their Stop KillerAI story. Visualizing Palestine is an organisation which uses data and research to visually communicate Palestinian experiences to provoke narrative change. Their Stop Killer AI story demonstrates how the mass surveillance apparatus that touches every aspect of Palestinian life had been weaponised in a new, and especially lethal way. The scroll-story merges interactive graphics and research to create a compelling online experience that demystifies how Lavender operates and how the Israeli army used it to enable and justify the mass killing of Palestinians civilians in Gaza.

Stop Killer Robots continues to monitor the use of oppressive technology in Palestine and around the world. Our research and monitoring team Automated Decision Research contributed to the background research that informed StopKillerAI. Ahead of our upcoming episode of Digital Dehumanisation which focuses on Visualizing Palestine’s work, the Lavender system, and oppressive technology in Palestine, we sat down with Nate Wright a software developer and digital producer, who worked with Visualizing Palestine to develop the StopKillerAI story to discuss the project, his background, and the power of digital storytelling.

1) Tell us about your background and how you got into this sort of work.

I came of age in that brief window around the 2000s when the internet was still full of hobbyists, and I learned as a teenager how to code my own website. It was a lucky break, really. I went on to live in Palestine as a young peace activist and later worked as a journalist in the region. But when I eventually settled in Scotland, software development was a convenient career option.

I only landed on digital storytelling after a decade of professional experience in software development. For me, it is a great way to bring together my technical skills with my interest in activism, journalism, conflict and social change.

2) What other digital stories have you worked on?

I’ve contributed to a couple pieces for Forensic Architecture and The Ferret, but the most creative stories have been for Visualizing Palestine. The project I am most proud of is wehaddreams.com, which was made in one week during the early months of the genocide. It is extremely simple – both technically and artistically – but effective precisely because it is handled with a light touch. I call it a “tribute” rather than a “story”. When I made it, I couldn’t imagine that we’d be here almost a year later with no end to the killing in sight.

3) What inspired you to get involved with Visualizing Palestine? What do you enjoy about working for this organisation?

It is pretty rare for me to find a project that aligns so well with my politics, artistic sensibilities, and basic competencies. That’s a fancy way of saying I get to do something I care about but also something that I enjoy and something that I feel like I’m actually good at doing. I’m a big believer in the idea that activism has to be fun, or rewarding, or engaging in some way. It can’t be sustained by altruism alone. And working on these projects with Visualizing Palestine is all of these things for me.

4) What was the process like for creating the Stop Killer AI scroll story?

It was inspired by the investigative reporting of +972, an independent magazine run by Palestinian and Israeli journalists. They exposed what little we know about the Lavender and Where’s Daddy software that Israel used to accelerate the bombing of thousands of people in Gaza, and why these targeting tools likely contributed to the mass targeting of family homes.

After reading the article, I was enraged. I couldn’t imagine an abuse of machine learning technology in war that was more widely predicted in books, television, film, and expert circles. I reached out to Visualizing Palestine and began putting together the visual scaffold of the story – the command-line interface in which the story unfolds.

Jessica Anderson [Visualizing Palestine’s Deputy Director] and Aline Batarseh [Visualizing Palestine’s Executive Director] helped draft and refine the script while I figured out the technical details. They’re good at bringing in a broader perspective to the script writing. As a technologist, I was focused on the misuse of machine learning – specifically the wanton manipulation of the targeting thresholds that +972 reported. But they rightly refocused on the broader story of the use of AI to accelerate the killing.

There’s probably a lot of overlap with the Stop Killer Robots Campaign. People like me who focus on narrow technological problems often emphasise a tool’s accuracy or inaccuracy. But tools – weapons – are always misused in the context of war. That’s why I think bans are more useful than regulations which try to outline when a weapon can be used.

5) What is the importance of digital storytelling in activist spaces, both in the context of Visualizing Palestines work and more broadly?

I don’t know! I leave the strategy to other people. Storytelling is what I use to think through and then speak about what I care about. In an ideal world, we’d all have deep ties to local communities where we’d talk about these things together, face-to-face, with people who we trust and who trust us to work together in good faith.

Instead we inhabit this weird digital public sphere where bad faith argumentation is the norm. Making these digital stories allows me to put something into that space that I’m proud of – a little craft, a little creativity, a little something that I hope meets people where they are and brings them something that endures after they put down their phone.

Explore Visualizing Palestine’s Stop Killer AI story

Learn more about Digital Dehumanisation

About Nate Wright:

Nate Wright is a software developer and digital producer who makes stories, apps, and websites for journalists, campaigners and activists. He lives in Edinburgh and can be found online at https://notthisway.com.